Does familiarity breed contempt? No, in fact it’s the opposite, according to “mere-exposure effect” and this psychological phenomenon has important lessons for leaders

We were working with a large infrastructure company who were digitalising their network.

One senior leader mentioned that he was surprised that some of the most vehement reactions to change came about when his team discovered that the interface on the screens in their control rooms had changed. Why our client asked us, was the reaction to this small change so strong? After all, there was no risk of job losses.

There are two related psychological theories that could explain this adverse reaction to an apparently small change. The first is loss aversion. Very simply, this proven psychological principle says that we prefer to avoid losing something more than we like acquiring something of equivalent value. Essentially, the pain of losing £100 is greater than the joy of getting it. That’s why marketers will allow you to try a service free of charge for a period so that you’ll get used to it. Then, when the trial period comes to an end the pain of losing the service will, they hope, encourage you to sign for it for a longer period.

Slightly less well known, but equally powerful is the “mere-exposure effect.” This highlights the way in which we typically form an attachment to something, not because of its inherent value or appeal, but simply because we’ve been exposed to it for some time. Ever hear a song and decide at first that you don’t like it but then, as you hear it played again and again you find it growing on you? That’s the mere-exposure effect.

Familiar and safe

In one experiment researchers from the University of Pittsburgh arranged for four women who looked roughly similar, to go to college lectures. One woman attended 15 times, one went 10 times, with the third it was five times and in the final case, the woman didn’t go at all. At the end of term, the students were presented with images of the four women and asked to judge them in terms of physical appearance. Based on no other information or interaction, the class decided that the most attractive woman was the one that they’d seen most frequently in the class.

As is so often the case, the causes of loss aversion and the mere-exposure effect dates back to our cave-dwelling ancestors once more. Life was brutal and short for them and so things that were familiar, would also often equal safe. Objects and experiences that were new and different could easily contain risk or threat and therefore they set alarm bells ringing and would fire up the amygdala, the “fight or flight” part of the brain. Simply navigating this new terrain would take time and effort that could be better used elsewhere – a feeling that we’re familiar with today.

The more you see it, the more you like it

On the other hand, if our ancestors found themselves confronted with something familiar, they – like us – would experience activity in the parietal or occipital cortices of the brain. Both of these are associated with the release of oxytocin, the bonding neurohormone.

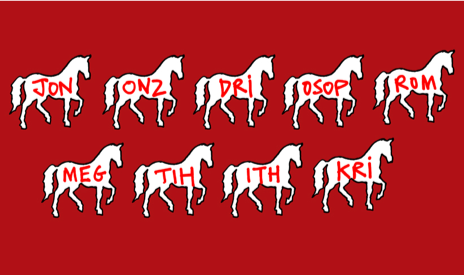

In workshops we often do this simple thought experiment: imagine that we’re all taking part in an office sweepstake on a horse race. We all chip in the money, and you get the winnings if you pick a horse that comes in first, second or third. Imagine that the odds on all of them are equal. Take a look at the horses and pick out your top, one, two and three. Have a go at this now – which would you choose?

If Meg, Jon or Rom, featured in your top three, you’re like most of us.

When we impose change on an employee, we’re placing them in an unfamiliar landscape.

However, there’s a wealth of evidence to suggest that people do readily accept changes that build on things that are already familiar to them. Sure, we do like things that are new and different such as a new holiday destination. However, there’s always that element of risk taking and anxiety and when something as fundamental and essential as our job is at stake, the idea of something new can be even more frightening.

Building on what people already know

Even with that first visit to somewhere, in reality we like things that build on what we know and trust. Change is constant and can often be unsettling or disturbing. However, bearing in mind the effect that the loss aversion and mere exposure can have on people and building on what they already know, together with effective consultation can help make that change not only bearable but positive and empowering.

One final example. We were always told that, in the middle of the 20th century, the Beatles revolutionised popular music. In fact, they were smart enough to introduce something new just at the right time. In other words, they introduced an innovation to what was already familiar to people. If the Beatles had released their truly revolutionary track Tomorrow Never Knows to an unsuspecting audience in 1962, we almost certainly, would never had heard of them again. They might have seemed shocking at the time but actually, the Beatles massive success is more proof of our love of the familiar.